In the life sciences, 3D bioprinting allows the creation of tissue-like architectures that better resemble human physiology than traditional 2D systems [1].

Anecdote

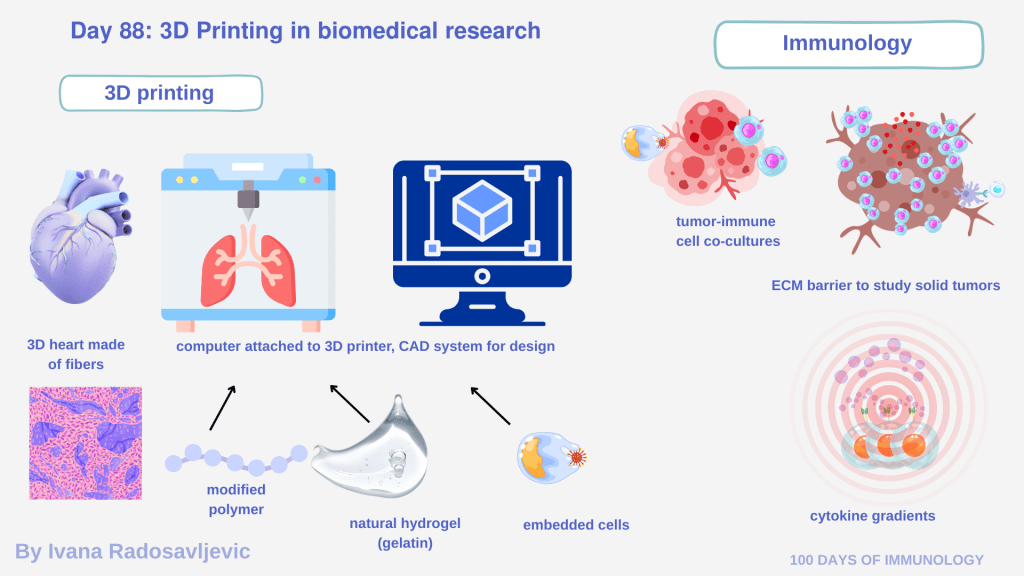

During my masters training, I worked in a lab that 3D-printed human heart constructs to study optogenetic control of cardiac tissue. I remember holding a small, purple-fibered heart in my hands: a demonstration that biology, physics, and engineering can converge into something beautiful. Later, I joined another university group where 3D printing was used not for tissues, but for custom experimental plates – a novel concept aimed at improving assay reproducibility and throughput. I hope this technology will soon be patented and translated to the market.

𝗛𝗼𝘄 𝟯𝗗 𝗕𝗶𝗼𝗽𝗿𝗶𝗻𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗪𝗼𝗿𝗸𝘀

Most bioprinters are computer-guided systems connected to dedicated software. Researchers design constructs using CAD-based programs, where geometry, pore size, layer thickness, and spatial cell distribution are digitally defined. These designs are then translated into machine instructions [2].

𝗖𝗼𝗺𝗺𝗼𝗻 𝗯𝗶𝗼𝗶𝗻𝗸𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗺𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗮𝗹𝘀 𝗶𝗻𝗰𝗹𝘂𝗱𝗲:

• Natural hydrogels: alginate, collagen, matrigel

• Modified polymers: GelMA (gelatin methacrylate), PEG-based hydrogels

• Composite bioinks: combining ECM proteins with living cells

• Cells: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, immune cells… Crosslinking (ionic, or UV-mediated) stabilizes the structure while preserving cell viability [3].

𝗔𝗽𝗽𝗹𝗶𝗰𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗜𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗼𝗹𝗼𝗴𝘆

3D printing enables:

• Tumor–immune co-cultures with defined spatial architecture

• ECM-rich barriers mimicking immune exclusion in solid tumors

• Vascularized constructs

• Cytokine or chemokine gradients embedded into the scaffold

• For CAR-T, CAR-NK, or M0-based therapies, 3D-printed models allow investigation of immune infiltration, exhaustion, cytokine release [4].

𝗦𝗽𝗲𝗰𝘂𝗹𝗮𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗲 𝗛𝘆𝗽𝗼𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘀𝗶𝘀

Imagine printing modular immune ecosystems: tumor cells embedded in stromal scaffolds, endothelial channels (blood vessels) guiding immune migration, and biosensors reporting cytokine flux in real time. That could help optimize CAR designs, dosing strategies, and safety profiles before entering costly 𝘪𝘯 𝘷𝘪𝘷𝘰 studies or clinical trials.

𝗤𝘂𝗲𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲 Audience

If your department suddenly received a 3D bioprinter, what would you design first?

Stay tuned for 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟴𝟵: 𝗘𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗟𝗮𝗯𝗼𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘆 𝗔𝗰𝗿𝗼𝗻𝘆𝗺𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗕𝗶𝗼𝗺𝗲𝗱𝗶𝗰𝗮l 𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗲𝗮𝗿𝗰𝗵

𝗥𝗲𝗳𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲𝘀

1. DOI: 10.1038/nbt.2958

2. DOI: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.11.008

3. DOI: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/1/013001

4. DOI: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.03.009

#3DBioprinting #Bioengineering #Immunology #CAR_T #Organoids #Optogenetics #TranslationalResearch #FutureOfBiotech #100DaysofImmunology